My quest to meet freaks, weirdo’s, people using useful skills USEFULLY, non-conventional humans, artists (who may or may not be human), continues. Today, however, I must return to a fascinating couple that I introduced in my recent post on the Food Farm. They are Duluth’s very own “odd couple.” The show Green Acres comes to mind, but in an earthier, more down-to-earth way.

Janaki Fisher-Merritt and Annie Dugan, the husband and wife team that own the Food Farm CSA, are so unique and remarkable that I find myself feeling unspeakably grateful for them on behalf of our entire community. I admit this is an odd thing to say. Truth, whether written or spoken, often is. We are blessed to have them here. Both individually and as a couple, they embody a philosophy that many of us are striving with all of our collective might to recover:

Our bodies are more than just sacks of flesh made to carry our brains around. They should be in partnership. (Loose quotation of Wendell Berry by Annie)

Annie grew up as a city girl in downtown Ann Arbor, Michigan, which she describes as a mid-size college town like Madison, Wisconsin, with eclectic variety and a large Bohemian-type crowd. She loved the city for the nightlife, exposure to art of all varieties, and for the ability to walk nearly anywhere she needed to be. This was foundational for her ultimate career as a curator and advocate for the arts. I find it incredibly ironic that she married a farmer. While her work-life is focused downtown, her family life is spent down-on-the-farm. She currently serves as Executive and Artistic Director for the Duluth Art Institute (housed in the Depot), and easily could have become a big-city art snob if that sort of ambition had captured her heart. Annie holds a master’s degree from Columbia University in New York City, after all.

For someone with her credentials and experience in the art world (as well as being an accomplished competitive jigsaw puzzler!), she is incredibly approachable. It’s rather disarming, and a real breath of fresh air. I showed up at her office adjacent to the current batch of artwork on display to ask a few questions, unshaven and sweaty from the bike ride, and found her to be friendly, thoughtful, vivacious, and youthfully alive (almost childlike – in a good way). She purchased my book at full price, and greeted me as a fellow creator/artist. It’s difficult to explain, but when someone in an important and influential role like her’s treats someone like me (whose book sales still creep up one or two at a time) as a colleague or equal in some way, it immediately puts me at ease. Mutual respect and admiration for the talents of one another are powerful feelings. Frankly, this is the sort of elixir that could cure many of society’s most pernicious ailments. She is completely non-judgmental. Genuine. Encouraging. Authentic. A lovely woman inside and out. This is the sort of person that can bring art to a larger body of people, many of whom previously gave up on the arts as elitist and far too up-in-the-clouds for the real world.

Surely you have someone like this in your community, whether titled or not. I urge you to identify and become their friend TODAY. Dugan empowers artists throughout the community. She encourages them to grow and develop, promotes enthusiasm for the arts in Duluth, and endeavors to make the DAI a catalyst for creativity in our community.

Her work, at least conceptually, is similar to Janaki’s role as the current caretaker and guider of the Food Farm. I hesitate to use the word owner, because he is mindful of passing along the farm in a condition even better than he found it as his life’s work. Janaki and Annie each cultivate in their own uniquely important fields of expertise and passion.

They are a fascinating couple, perfectly balanced in the arts and in local food production. It’s difficult for me to conceive of another area outside of Duluth that is more enthusiastic for a bona fide artistic community and also for local agriculture. I mean, seriously, these two are involved in the literal heart of each of these powerful movements that are transforming Duluth and the Twin Ports from a burned out post-industrial metropolitan area into the thriving city that we are all proud of today, even as we labor together to place the footings required for a brighter future.

The fact that they’ve been able to weld these two areas so effectively is, in my mind, emblematic of what has enabled their marriage to thrive. It’s difficult for me to conceive of a more potentially mismatched couple, in fact! Before agreeing to move to the sticks and marry Janaki, she had three simple demands:

- Delivery of the New York Times

- Access to high-speed Internet

- Reliable cell phone reception

None of these were available when the ultimatum was made, but all arrived soon thereafter as an apparent cosmic gift, though she did concede for a spell by biking to the Carlton library for email access.

A 30-inch stack of treasured sections pulled from the New York Times in her home appears to be a guilty pleasure (fittingly placed immediately to the right of the window looking out on the farm below), providing easy access to cutting-edge culture and ideas within the context of a working farm. Annie was horrified to hear that I saw this impressive pile during a recent lunch with her husband, but I found it to be endearing. From what I can gather, she has adjusted to rural life admirably. As a converted city-girl who maintains feet in both worlds, Dugan appreciates the peaceful setting while appearing to take little of it for granted. She claims to only miss one thing: the ability to bike and walk to nearly all her destinations.

Janaki is full of surprises as well. (Interestingly enough, he’s the middle child among brothers named Jason and Ben. Try figuring that one out!) I’ve never met another single individual in my entire life who has been more thankful for his college education, obtained at Carleton College (where he met Annie). I greatly appreciated the contrast between his perspective and my own. I wrestle with the notion that higher education may not be necessary for the majority of people, and chafe against the student-debt-bubble that will hopefully deflate rather than pop outright.

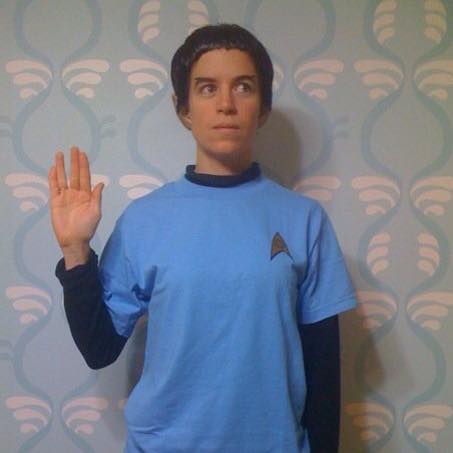

Janaki (pronounced John-a-key and seen astride the 1948 Case tractor pictured above that is still in use on the farm and affectionately referred to as Rhoda) is convinced that his degree at the private college was worth every penny. Disagreeing emphatically when I called his sociology and anthropology degree nearly worthless for farming, he points out that it has made him into a better businessman and communicator. Indeed, I must concede that it has. He is a unique breed of farmer that thrives as a philosopher, communicator, astute businessman, scientist with intimate knowledge of the carbon cycle, as a psychologist while motivating interns to do difficult and often-tedious work, and as a simple hard worker himself, who has to persevere in the context of a difficult environment.

His appreciation for an education steeped in the liberal arts is plowed into the next generation as well. Though he shoulders demands that would overcome lesser-beings with anxiety, he carves out significant time and energy to serve on Wrenshall’s school board. Now in his tenth year, in the middle of a third term in this position, he originally was elected as a write-in candidate. Try calculating the odds of a successful write-in campaign when voters must spell a name like Janaki Fisher-Merritt correctly. With precision. Any spelling error caused the vote to be tossed out.

A successful fight to keep a large oil pipeline off the organic farm’s property also validates Janaki’s education. More than a dozen pipelines from Northern and Western North America (crude oil, gas, and natural gas) get funneled through Wrenshall. In fact, the second-largest tank of compressed natural gas on the continent quietly rests in this small, agricultural community. Needing to go around Lake Superior, Wrenshall is a key location for the pipeline industry. From there, the pipelines get directed toward Chicago or through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula on their way to the East Coast.

On August 1, 2012, the day after they successfully hosted the annual Free Range Film Festival, they received a letter notifying them of eminent domain proceedings for the future construction of a crude oil pipeline through the heart of their property. For the next six months Janaki devoted more than 20 hours a week fighting this by organizing a community outcry. He says his education felt intensely practical while enduring this moment of possibly the greatest stress on his life and future that he’ll ever face. The ability to strategize, analyze, communicate, wade into the legality of the proceedings, and to network throughout the community, he credits to a liberal arts education. He was, and is, still a young man that had only recently taken over the farm. Remarkably, this small family farm fought the corporation and won (along with the concerted efforts of others who were equally concerned). Though he has personally stepped back some from the ongoing endeavors out of necessity, they are still fighting the construction of this pipeline on the basis of need (they don’t wish to just push the problem off on someone else). Janaki is incredulous that a foreign company can be granted the power of eminent domain for a product that isn’t even staying here. The oil is just flowing through, and will not be processed in the small nearby refinery in Superior, Wisconsin. Apparently, one of the schemes is to ship crude through the Great Lakes with large oil-tankers as well. It’s difficult to argue with his perspective that the level of risk involved for us to facilitate a steady flow of oil is simply unnecessary, given the reality that the supply already coming out of the Bakken oilfields is outstripping demand and the industrial capacity to handle it effectively.

There is so much more that can be said about this thoroughly community-minded couple. Another example, and an entire book could and will be written some day, is their hosting of the Free Range Film Festival. Held in a beautiful old barn on property where Annie and Janaki lived when they were first married, it was sold to Annie’s parents (who moved here from Michigan) so the film festival could continue after they took up residence on the Food Farm itself. This quirky, whimsical festival, held in late July, has Annie and Janaki’s fingerprints all over it.

The notion of a film festival kind of sprang up organically. The century-old barn came along with the house that Janaki purchased at the age of 24. Not knowing what to do with the beautiful structure, he constructed a rudimentary screen out of Tyvek housewrap and watched movies in it with his friends on weekends. The next year, 2005, the film festival was launched along with the help of friends. Equipment has been upgraded impressively over the years. Billboard material was used as a screen for a while, but when a cinema closed in nearby Duluth, they obtained a more professional large screen, along with enormous speakers and amps. Interest in the Free Range Film Festival grows from year to year. Its success and impact on the community owes to Annie and Janaki’s perseverance, a childlike love of the arts, and a playfulness wherein they don’t take themselves too seriously. This latter point could be drawn out more, but suffice to say, they aren’t filled with an unhealthy notion of self-importance.

Our entire community enjoys the fruits of their many and diverse labors. We are all beneficiaries of their work, whether or not we taste of it directly. Annie and Janaki are a marvelous example of the satisfaction that comes from useful work that provides value. Both fields require tremendous effort and often-tedious work, which often contradicts the romanticized notions that the public has of them, but the fruits borne provide profound fulfillment and meaning for all. At the end of the day, if a community is unable or unwilling to produce much of its own art, entertainment, healthy food, and appreciation for local beauty in all its forms, it has lost its identity. This truth is inseparable from Duluth’s ongoing renaissance.

Two of my favorite people! Great write up. But what about Truman?

Yeah, the ongoing Truman Show will be a fun one to watch unfold. Due to popular demand I snuck the little cutie in with the photo on the bottom….